CAD + WebRTC

Early on, we knew we wanted to build an API for CAD using cloud GPUs doing the 3D rendering. This meant we needed to stream the video generated on the cloud to our clients. The web is full of streaming technologies, your web browser probably supports at least WebRTC, but it might also support HTTP Live Streaming (or HLS), and it also probably supports encoded video sent over HTTP. So, what is WebRTC and why does it work so well for our Design API?

The RTC in WebRTC stands for “Real-Time Communication”, which seems like what we want. The term real-time is kinda hard to define because it’s very contextual. For streaming video that means fast enough that you don’t notice any buffering. For something interactive, like a 3D scene you can move around, real-time means fast enough that video updates triggered by mouse movements happen so quickly that you can’t perceive any lag. The latter is exactly what we want, and luckily WebRTC supports both. WebRTC provides peer-to-peer communication, which differentiates it from other server-centric streaming technologies like HLS. WebRTC is really a set of rules about how to combine a bunch of other protocols together, some of which have been around for a while. Session Description Protocol (SDP) was standardized in 1998 1. Session Traversal Utilities for NAT (STUN) was standardized in 2008 2. And, Traversal Using Relays around NAT (TURN) was standardized in 2010 3. WebRTC itself is still fairly young, the RFC was first published in 2011, and only moved to recommended status in 2021 4.

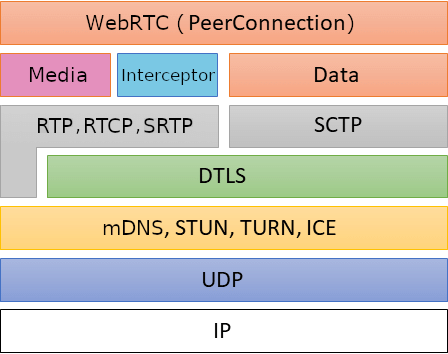

This helpful graphic from the Rust WebRTC library we use summarizes the different protocols in use and how they all really build on top of each other:

Near the top we can see “Media” and “Data”, the protocols below each are responsible for sending that type of data, or metadata about it. For example, RTP is the media itself, and RTCP is a set of messages that contain information about how a stream is performing, or if it’s failing. Below those is DTLS, which is encryption and easy to enable, so we do and you should too. Browsers treat this as required, but technically you could set up an unencrypted peer connection yourself, but that’s obviously not recommended. The next layer down is probably the most interesting as it handles some challenges with how computer networks are structured. A bunch of things exist in this layer, but the goal is pretty simple, initiate communication between two computers or peers.

The internet is made up of private and public networks, getting data to the correct computers when hopping between networks requires some extra care. This is called NAT, and both STUN and TURN reference it by name and are utilities for working with this aspect of modern networks. STUN helps you figure out your public IP address if you’re on a private network. TURN is a proxy between private and public networks. If you’re on the same network, you don’t actually need STUN or TURN of course. Two computers on the same network can communicate without NAT, assuming firewalls don’t get in the way. In these cases we can just use SDP to share server and client IPs and ports. This can even be on the same machine, something that makes local development work really nice.

There are a few hosted STUN and TURN services out there, and they’re great if you’re building some sort of peer-to-peer application, where the TURN server proxies both sides of a connection. But, for our purposes we are always sending video data from our servers, so it made a lot of sense early on to try to internalize this part of our infrastructure for both latency and to minimize the cost of bandwidth. So, we’re self-hosting a project called stunner that provides STUN and TURN as well as some other beneficial features on top like authentication for TURN sessions.

This entire set of tools and processes is called ICE or Interactive Connectivity Establishment. Now that we have all of these pieces of it in place, we can actually use them together to establish interactive connectivity. With the correct information and a TURN server, ICE can connect any two computers on the internet. The process of making sure both sides are willing to accept the connection, and facilitating the exchange of information needed is called signaling. WebRTC has pretty well-defined protocols and procedures for just about everything, except for signaling. But, rightfully so, signaling is very use-case specific and leaving this part up to each implementor makes the protocol very flexible! In our case, we use a persistent websocket connection to facilitate that exchange. Our modeling app gets sent the address for stunner so that it can establish ICE. Our server and our modeling app (or any client) then exchange their details. These details result in “candidate-pairs” that are all tested for connectivity in parallel. If any of them succeed, bi-directional communication is established using UDP!

Because WebRTC uses UDP for the underlying video transport, it’s very low latency. We want our modeling app to feel fast and responsive, so low latency was a requirement for us. The low latency also extends to a feature of WebRTC called data channels. This is very useful for making mouse movements and other user interactions feel as responsive as possible. We can send certain events along our very low latency data channel for the best experience. Of course, the downside of UDP is that it’s unreliable. Luckily, video encoders can be fairly tolerant to lost packets, and WebRTC’s use of RTP over UDP ensures ordered, loss-tolerant delivery. Failing that, WebRTC provides mechanisms to repair streams if too many packets are lost.

Our initial usage is very simple uni-directional sending of videos from servers to clients. But, WebRTC’s multiple peer support means we could easily share video with multiple collaborators on the same scene. Collaborators could each have their own view, or share one. WebRTC is very flexible and can support a lot of simultaneous video feeds.

Also, WebRTC support is fairly pervasive. All major browsers support WebRTC as of 2020 at the latest 5. WebRTC is also pretty good outside of browsers, with good library support in various languages. This broad support has also led to a lot of additional features in the protocol. Like quality of service metrics and messages. Google introduced the idea of WebRTC, has used it in various projects over time, like Google Meet, and Stadia, and has steadily made improvements to their Chrome browser to improve the experience.

Further reading:

If you're interested in more details on the challenges of NAT, Tailscale wrote a very detailed blog on the subject: https://tailscale.com/blog/how-nat-traversal-works/